MIT Anthropology Speaks Out — and Teaches — against Racism

MIT Anthropology

August 25, 2020

MIT Anthropology Speaks Out — and Teaches — against Racism

On June 1, 2020, MIT Anthropology posted a collectively crafted statement:

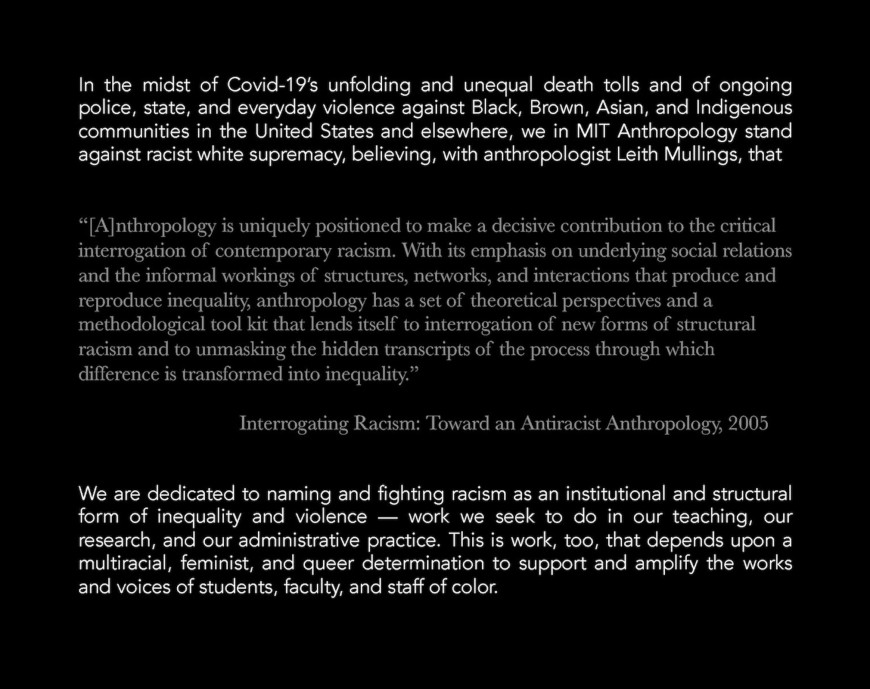

In the midst of Covid-19’s unfolding and unequal death tolls and of ongoing police, state, and everyday violence against Black, Brown, Asian, and Indigenous communities in the United States and elsewhere, we in MIT Anthropology stand against racist white supremacy, believing, with anthropologist Leith Mullings, that

"anthropology is uniquely positioned to make a decisive contribution to the critical interrogation of contemporary racism. With its emphasis on underlying social relations and the informal workings of structures, networks, and interactions that produce and reproduce inequality, anthropology has a set of theoretical perspectives and a methodological tool kit that lends itself to interrogation of new forms of structural racism and to unmasking the hidden transcripts of the process through which difference is transformed into inequality. This enterprise demands long-term ethnographic and historical research … [and] must be grounded in a critical interpretation of race not as a quality of people of color, but as an unequal relationship involving both accumulation and dispossession.”

From “Interrogating Racism: Toward an Antiracist Anthropology.” Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 34:667-693

We are dedicated to naming and fighting racism as an institutional and structural form of inequality and violence — work we seek to do in our teaching, our research, and our administrative practice, and work that depends upon a multiracial and feminist determination to support and amplify the works and voices of students, faculty, and staff of color.

Our statement, released in the wake of the police murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd — 2020 additions to a long string of U.S. police killings of Black people and others — names MIT Anthropology’s commitment to anti-racist practice and pedagogy. That commitment is always central to our work, but in an era in which the President of the United States is waging an open war on people of color, international students, women, LGBTQIA rights, immigrants, Indigenous people, and, through vilification of rigorous scientific inquiry, the very health of an entire polity, it seemed to us vital to put these words on the screen.

On June 10, MIT Anthropology joined an academic strike — #ShutDownAcademia#ShutDownSTEM — a day-long event that particularly asked "white and non-Black People of Color (NBPOC) to not only educate themselves, but to define a detailed plan of action to carry forward." With a number of us teaching classes on computing and culture, we renewed our dedication to advocating not only that MIT’s newly founded Schwartzman College of Computing expand its efforts to hire underrepresented faculty, but also that it work actively against racism and anti-blackness in the development of computer technologies themselves, a call we amplified from On Being Black in Computing During These Days. Postdoctoral Fellow Beth Semel spoke out against a top publisher’s plans to release a paper claiming to have pioneered an algorithm that could detect criminality based on facial biometrics, a claim, when it was first made in the 1870s, was already a study in racist pseudoscience. We directed colleagues’ attention to a scorecard tracking MIT’s response to the recommendations made not only by the Black Students Union and Black Graduate Students Association in 2015, but also going back to the 2010 Hammond Report on the Initiative for Faculty Race and Diversity and the 2011 Report on the Status of Women Faculty in the Schools of Science and Engineering. We in the humanistic social sciences and arts joined — and join — our colleagues in the sciences and engineering in holding MIT accountable for addressing systemic racism at MIT as well as in confronting the persistent sexism, homophobia, and transphobia that still exists at our institute. We also support MIT’s work with the MIT Indigenous Peoples Advocacy Committee (IPAC) and MIT's American Indian Science and Engineering Society (AISES) to create a meaningful Indigenous Land Acknowledgement statement, one that can be used to address and fight continued dispossession in Massachusetts.

Closer to the discipline of anthropology, we have widely promoted the Association of Black Anthropologists’ Statement Against Police Violence and Anti-Black Racism as well as the Association of Latina/o & Latinx Anthropologists Statement Against Anti-Black Racism and are dedicated to working with one another and with students to face our discipline’s legacy as one wound together with race, racism, and whiteness, even amidst its vital anti-racist work. That is work we seek to do in helping one another craft syllabi, strategize about how best to activate strong and safe classroom conversation about racism, and generate strategies for supporting early career scholars (on which last, we are informed by, among other sources, the #BlackintheIvory discussion on Twitter). This is work that takes aim at anti-blackness as a core feature of U.S. American racism and that also recognizes that the discipline must continue to confront its complicity with anti-Indigenous dispossession and with a long history of marginalizing scholars of Asian and Hispanic/Latinx identity and community. It is work, too, that we do — and are dedicated to intensifying — in our classes. MIT Anthropology classes precisely on these topics include:

Race and Migration in Europe

Africa and the Politics of Knowledge

Images of Asian Women

Gender, Race and Environmental Politics

Hacking from the South

The Science of Race, Sex, and Gender

It is not only MIT Anthropology faculty who are dedicated to the cause of anti-racism. Our students and alum are doing important work in this domain. Anthropology alum Gabby Ballard SB ’19 spoke at a 2020 Act Now to Stop War and End Racism rally. David Lowry SB ’07, Associate Professor of Anthropology at Biola University, continues to write and work on behalf of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, of which he is a member.

At a time when racism and white supremacy are the sharp edge of rising fascist movements in the United States, it is vital to put anthropology to work in the service of justice.